An everyday situation, a harmless stimulusEin Reiz, häufig auch Stimulus genannt, ist eine äußere oder innere Einwirkung, die ein Lebewesen wahrnimmt und die eine Reaktion auslösen kann, aber nicht muss. Reize können aus der Umwelt... » Weiterlesen, and yet the horse suddenly explodes and reacts in a way that seems completely out of proportion. It disengages from training, becomes agitated, tries to flee, or in the worst case even shows aggressive behavior. What may look like an overreaction is often the final result of a chain of invisible stressStress ist eine körperliche und emotionale Reaktion auf eine Herausforderung, Belastung oder Bedrohung. Er entsteht, wenn ein Lebewesen eine Situation als herausfordernd oder überwältigend wahrnimmt und sich anpassen muss. Stress... » Weiterlesen and a buildup of arousal that the nervous system can no longer regulate: triggerEin Trigger ist ein spezifischer Reiz (Stimulus), der eine starke emotionale oder unkontrollierte Reaktion bei einem Tier auslöst. Während ein allgemeiner Reiz neutral sein kann und erst durch Lernen eine... » Weiterlesen stacking.

Especially in training based on positive reinforcement, where cooperation and emotional stability form the foundation for learning, rising stress levels can quietly undermine the entire process. Horses are skilled at adapting. They compensate until they no longer can..

Understanding trigger stacking in horses

The term trigger stacking comes from human psychology, specifically from trauma research. It describes how the nervous system can become overwhelmed by a series of emotional or sensory stimuli. A single trigger might be manageable, but when several stressful events happen close together, the system can lose its ability to cope.

The idea was later adopted in dog training, where it became clear that dogs often react unexpectedly when faced with multiple stressors in succession. The problem isn’t any one trigger on its own, but the cumulative load they place on the animal.

In horse training, the term is still not widely used, even though horses are just as vulnerable to the effects of accumulated stress. One of the key challenges is that horses tend to internalize tension. They’re remarkably good at compensating for discomfort and only give subtle signs when something is wrong. As a result, rising stress levels often go unnoticed until the horse suddenly shuts down or reacts dramatically.

Trigger stacking means that several minor triggers, each seemingly harmless on their own, can lead to overload when they occur together or in close sequence. These triggers can take many forms: a loud sound, a change in environment, a new task, social tension in the herd, or even physical discomfort. What matters most is whether the horse has had enough time and opportunity to recover and regulate itself between these experiences.

If that recovery doesn’t happen, the nervous system stays activated. Eventually, the horse may react in ways that seem out of context or excessive. But in truth, the outburst is just the last drop in an already overflowing bucket. In practice, this might look like a horse becoming restless while being led, snapping during haltering, zoning out during training, or suddenly panicking. These reactions rarely come out of nowhere. More often, they are the visible tip of a much deeper process. Trigger stacking builds quietly, often out of sight, until it finally breaks the surface.

Understanding stress responses: A look inside the nervous system

To truly understand trigger stacking, it is not enough to focus solely on behavior. A clear understanding of the biological processes inside the horse’s body is just as essential. When a stimulus is perceived as threatening or uncomfortable, the horse responds immediately by activating the sympathetic nervous system. This part of the autonomic nervous system prepares the body to mobilize energy in situations of potential danger.

Within seconds, adrenaline is released. This hormone increases heart rate, directs blood flow to the large muscle groups, narrows blood vessels in the skin and digestive system, and increases respiratory rate. The body prepares for fightFight-Response ist eine Strategie zur Stressbewältigung (Coping-Strategie), bei der das Tier aktiv gegen eine Bedrohung vorgeht. Es versucht, sich durch Drohgebärden oder aggressives Verhalten zu verteidigen, anstatt zu fliehen oder... » Weiterlesen or flightFlight ist eine Strategie zur Stressbewältigung (Coping-Strategie), bei der das Tier die Gefahr durch Weglaufen oder Ausweichen vermeidet. Diese Strategie ist oft die erste Wahl, wenn das Tier eine Möglichkeit... » Weiterlesen. This reaction is ancient and serves a vital survival function.

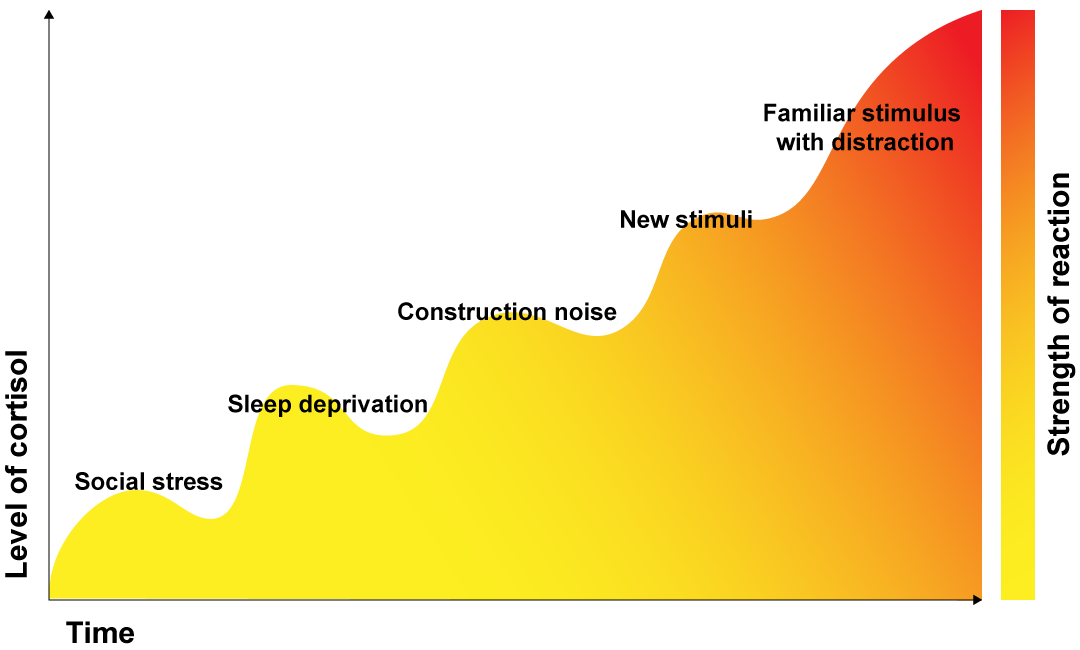

If the stimulus does not subside quickly, or if several stressors occur in close succession, cortisol is released as well. Cortisol acts more slowly than adrenaline but has longer-lasting effects. It helps the body stay alert and functional for a longer period, but it also takes a toll. Cortisol suppresses digestion, healing, the immune system, and emotional balance. Its release indicates that the body is in a state of ongoing alarm.

One key detail: cortisol is broken down much more slowly than adrenaline. While adrenaline disappears within 10 to 30 minutes, cortisol can remain active in the body for up to 24 hours, depending on the horse’s health, fitness, past experiences, diet, and individual stress sensitivity.

During this time, arousal continues to rise while the horse’s ability to process stimuli and regulate itself steadily declines. The threshold for reacting to new input drops. A stimulus that was easily manageable yesterday may cause a strong reaction today.

At the same time, controlControl (Kontrolle) ist ein fundamentales Grundbedürfnis, da sie einem Individuum die Möglichkeit gibt, aktiv Einfluss auf seine Umwelt und sein eigenes Verhalten zu nehmen. Kontrolle bedeutet, dass Handlungen vorhersehbare und... » Weiterlesen shifts within the brain. The limbic system takes over, especially the amygdala, which is responsible for evaluating emotional threats. It becomes increasingly sensitive, especially to anything new or uncertain. Meanwhile, activity in the prefrontal cortex, the area that supports conscious judgment, impulse control, and learning, decreases.

This means the horse is no longer able to clearly distinguish between safe and unsafe. It reacts more strongly to sights, sounds, or physical sensations that would otherwise go unnoticed. Its behavior may appear sudden or exaggerated, but in reality, it is a logical response to inner overload.

In this state, true learning becomes nearly impossible. These are not moments of defiance, but moments in which the horse simply cannot cope.

Chronic stress: when trigger stacking becomes the norm

A single stressful moment is usually manageable as long as the body has a chance to recover afterward and return to a calm state. The problem arises when that recovery does not take place and the level of arousal remains elevated over time, as is often the case with trigger stacking.

When a horse experiences repeated stress without sufficient opportunity to regulate and decompress, the cortisol system stays active. The body remains in a constant state of alert, the nervous system becomes more sensitive, the threshold for stimulation lowers, and resilience fades. Horses in this state often seem restless, distracted, or overly sensitive. They may have trouble calming down or overreact to small changes in their environment. Some develop stereotypical behaviors such as weaving or cribbing as a copingEine Coping-Strategie ist eine individuelle Bewältigungsstrategie, mit der ein Tier oder Mensch auf Stress, Angst oder herausfordernde Situationen reagiert. Diese Strategien sind evolutionär verankert und helfen, Gefahren zu bewältigen oder... » Weiterlesen mechanism. Others withdraw and appear indifferent or emotionally absent. Some may suddenly become “difficult” for no apparent reason. All of these behavioral patterns can be signs of the same underlying issue: a chronically overloaded nervous system that no longer finds its way back to balance.

Trigger stacking is not just a short-term reaction. It can build up slowly over days, weeks, or even months and have a profound effect on how a horse perceives, learns, and responds to the world. That is why it is so important to design the horse’s living conditions in a way that supports its basic needs. Unmet needs are one of the most common sources of everyday stress. A horse that is constantly operating on a background level of tension is unable to truly relax. It lives in a state of quiet overload, often without anyone noticing. One of the biggest challenges with trigger stacking is that we only see a small window into the horse’s daily life.

Even if we spend time at the barn every day and are deeply involved in our horse’s careDas Care-System ist eines der sieben primären emotionalen Systeme aus Jaak Panksepps Konzept der Affective Neuroscience. Es ist für Fürsorgeverhalten und soziale Bindungen verantwortlich. Es wird durch das Hormon Oxytocin... » Weiterlesen, we usually only see a few hours out of the full twenty-four. The rest of the time, the horse lives in its own environment, within the routines of its herd, in the pasture or the stall, influenced by things we cannot observe or control. And yet, it is exactly there that many of the experiences take place which shape its emotional well-being.

A horse might have spent the night unable to sleep because a dominant herd member kept it on edge. It might have felt unsafe during feeding because the space was too narrow or the setup too chaotic. It could be experiencing pain that is not immediately visible from the outside. All of these experiences linger. When we arrive the next day and begin a training session that we consider light or routine, the horse might already be mentally and emotionally strained. What follows may look like an unexpected reaction, but it is simply the result of accumulated tension.

That is why it is so essential to remember that we never start from zero. Every horse brings its own story into every training session. Not just from the past few months, but from yesterday, from last night, and from the moments just before we arrived. The more aware we become of this hidden background, the better equipped we are to avoid overload, build trust, and support the horse’s ability to learn and grow in a safe and meaningful way.

Thoughtful training strategies as a key to reducing stress

Trigger stacking can begin quietly in a horse’s daily life. But training itself can also become a source of overload. It does not take dramatic events for stress to accumulate. A series of small demands, unfamiliar sensory input or a slightly unclear structure can gradually overwhelm the nervous system. This kind of strain does not appear out of nowhere. It builds step by step. The less we pay attention, the greater the risk becomes.

This creeping overload is not only caused by external stimuli. When basic needs are not met, they can significantly impact the horse’s ability to engage in training. Hunger, pain, fatigue or inner tension can all act as stressors, even before the training session begins. If we then add new challenges without recognizing and addressing this underlying strain, the situation can quickly escalate. Stress is not always visible, and that is what makes it so hard to recognize during training.

The exercises themselves also need to be structured in a way that supports the horse’s emotional state. It is not just about how difficult a task is, but about the context in which it takes place. A seemingly simple task can become too much if it is introduced in a new environment, after a tiring day or in a situation filled with distractions.

A well-thought-out training plan takes these factors into account. Environmental elements that seem irrelevant to us, such as loud sounds, unfamiliar objects or the presence of a new horse, can already affect the horse’s emotional balance. If a new or still uncertain task is introduced on top of that, the situation can quickly exceed the horse’s capacity to cope. Even exercises the horse knows well can become overwhelming when its system is already under pressure or when the situation is unfamiliar.

A behavior is not reliable just because it works under familiar conditions. For a response to be stable and trustworthy, it has to be practiced in a variety of contexts. That means transferring familiar exercises to new situations carefully and avoiding sudden increases in difficulty. It is not that every change is a problem, but every new challenge should be introduced with awareness and preparation.

Participation in training: choice as a foundation for emotional safety

A training approach that avoids overwhelm does not begin with picking the right exercises or finding the ideal timingTiming bezeichnet im Clickertraining und in der positiven Verstärkung den genauen Moment, in dem ein Markersignal (z. B. ein Click) oder eine Belohnung gegeben wird. Präzises Timing ist entscheidend, da... » Weiterlesen. It begins with the attitude we bring to our horse. A key part of this is how much room we give the horse to actively participate in training. Choice can be a vital building block for creating emotional stability and genuine trust. It strengthens the horse’s willingness to cooperate, supports a sense of control, and makes training more transparent and safer for both horse and human.

One of the most important ways horses communicate during training is through their body language. Facial expression, posture, muscle tension and the way a horse moves often reveal how it feels even before it reacts more clearly. Narrowed nostrils, a tense jaw, a fixed gaze, shallow breathing or frequent blinking are subtle signalsEin Signal ist ein Zeichen oder Reiz, der für das Tier eine Bedeutung hat und ein Verhalten auslöst oder einen emotionalen Status hervorruft. Es zeigt dem Tier an, dass es... » Weiterlesen of inner stress. If we learn to see and respect these early signs, we are no longer waiting for resistance or refusal before we adapt the situation. Instead, we are already listening before the horse has to speak louder.

Another way to make choice visible and build it into training is through cooperative signals. These are clearly defined behaviors that indicate the horse is willing to participate in a specific task. For example, it might stand still in a certain position for grooming, approach a targetEin Target ist ein sichtbares Objekt oder eine Körperstelle, auf die das Tier gezielt reagieren soll, indem es sie berührt oder folgt. Es dient als Orientierungshilfe im Training und ermöglicht... » Weiterlesen voluntarily, or actively signal that it’s ready for the next step. These behaviors make the horse’s agreement visible and create a reliable entry point into what comes next.

Of course, not every training situation needs its own cooperative signal. But especially in new, potentially uncomfortable or demanding situations, such signals are a powerful way to build predictability and safety. Well established foundation behaviors, such as so-called default behaviors like standing still – facing forward, also serve an important dual function. They offer a calm starting point that gives orientation and security, and they also act as an emotional early warning system. If a behavior like the default behaviorEin Default Behavior (Basisverhalten) ist ein Verhalten, das ein Tier von sich aus zeigt, wenn es unsicher ist, welche Reaktion gerade gefragt ist. Es dient als eine Art „Standardeinstellung“ oder... » Weiterlesen, which is usually shown reliably and willingly, suddenly breaks down or stalls without a change in context, this can point to emotional stress or uncertainty.

When horses learn that their decisions matter, that their behavior has consequences and that “no” is an acceptable answer, they begin to develop a sense of agency. And this sense of control is one of the strongest buffers against stress. It makes horses more resilient even when new or challenging stimuli arise. A horse that knows it has a say is better able to cope than one that always has to adapt. We cannot prevent trigger stacking completely, but by offering real choice, we can reduce its frequency, intensity and impact.

hat to do when trigger stacking has already happened

Even with the best planning and careful observation, things can pile up. Sometimes, it is not one big event that tips the balance, but many small moments that quietly build up tension in the horse’s nervous system. When trigger stacking becomes visible, it is no longer time for more training steps. It is time to pause and shift focus. From now on, it is not about learning, it is about managementManagement im Training bezeichnet die gezielte Gestaltung der Umgebung und der Trainingsbedingungen, um das Lernen des Tieres zu erleichtern und unerwünschtes Verhalten zu vermeiden. Durch eine durchdachte Planung und Kontrolle... » Weiterlesen.

In that state, the horse’s system is no longer open for input. New cues, corrections, or tasks are not processed as intended, but instead add more pressure. Continuing to train risks creating negative associations and undermining trust, even if everything seems technically correct on paper.

Instead, the goal should be to restore a sense of safety, for the horse and for everyone involved. That means reducing stimuli, creating distance when needed, and giving the horse space to regulate itself. What helps depends on the individual horse: a change of location, a break without expectations, relaxed movement, time away from pressure or simply a few minutes of shared stillness. Some horses find calm in a familiar routine or in returning to a simple behavior that does not demand effort and feels safe. Others settle when they are allowed to move freely, sniff, graze or just take in their surroundings. Slow exploration without a task can do more to lower arousal than any carefully planned training step. The better you know your horse’s individual strategies, the more helpful and effective your support will be.

In moments like these, calling it a day is not giving up. It is a sign of clarity and care. You are showing your horse that its feelings matter, that you are listening and willing to respond. That kind of trust is more valuable than any completed training session. And it helps prevent situations from escalating. Because the longer that inner tension simmers, the more likely it is to spill over in ways that can become unsafe – for both horse and human.

Later on, it helps to look back calmly. Which triggers may have overlapped? Were there early signs you missed? Was the session maybe too ambitious or your horse just not in the right headspace that day? These reflections are not about blame. They are the first step toward building better awareness and creating more supportive training situations in the future.

Understanding stress as a whole and responding with responsibility

Trigger stacking is a clear sign that a horse’s emotional balance has already started to shift. It shows that the stress system is overwhelmed, sometimes by a single moment and sometimes by a slow buildup of unnoticed strain. Anyone working with horses needs to understand stress not just as something visible on the outside but as what it truly is on a biological level – an internal imbalance that influences behavior, learning, health and the quality of the relationship between horse and human.

The better we understand how stress develops in the body and in behavior, the more effectively we can prevent it or respond in ways that help the horse find balance again. This does not mean avoiding all challenges or wrapping the horse in cotton wool. It means staying observant, making thoughtful decisions and being flexible. It means recognizing that training plans, the horse’s physical and emotional condition, environmental influences, previous experiences, and the relationship itself are all part of the same system and deserve equal attention.

Trigger stacking invites us to look more closely. It gives us the chance to shape a learning environment where horses can develop without being pushed beyond their limits. This requires smart training structures, real communication and respectful choices that support the horse’s confidence and well-being.

Not every situation of overload can be prevented. But every moment of awareness, every pause and every thoughtful response helps stabilize the horse emotionally and supports long-term resilience. Those who understand trigger stacking for what it truly is – a signal that something has become too much – can turn it into an opportunity for growth. Because progress begins when observation becomes more important than performance.

I put a lot of heart and time into writing my articles to provide valuable information about positive reinforcement and horse-friendly training. If you enjoyed this post, I would be delighted if you would share it as a small thank you and so that even more people can benefit from this knowledge.